What Every General Counsel Needs to Know About the Intelligence Cycle

Because general counsel are involved in the megadeals, allegations of wrongdoing, and bet-the-company litigation that carry the greatest exposure for the company, general counsel need to understand intelligence investigations and the use of the intelligence cycle.

To develop policy and make informed decisions, heads of state look to the heads of their intelligence agencies for answers to critical questions. To protect the company against legal, regulatory, and reputational harm, companies should do the same. Because general counsel are involved in the megadeals, allegations of wrongdoing, and bet-the-company litigation that carry the greatest exposure for the company, general counsel need to understand intelligence investigations and the use of the intelligence cycle.

An Intelligence Investigation Is Not a Background Investigation

Good intelligence work is not an Internet search, a public records database search, or a background investigation. Good intelligence work is about being able to find the dots, connect the dots, and articulately report on the picture that emerges.

The Intelligence Cycle Works Because It Is an Iterative, Consultative Process

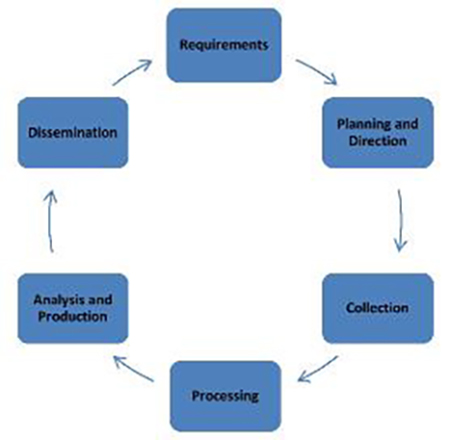

To produce accurate, reliable intelligence, agencies use a process known simply as the Intelligence Cycle. The accompanying illustration depicts how the intelligence cycle works:

Requirements. The client is the first and most important person in the intelligence cycle. The client sets the requirements and establishes what must be obtained and what questions must be answered. At the outset of the investigation, there needs to be a conversation between the client and the investigators about why the investigation is being requested. In the corporate context, if investigative due diligence is needed in support of a merger or acquisition, then the deal, the parties, and any unique concerns need to be understood. If an internal investigation is required, then the allegations need to be understood. If the company is in litigation, then the pleadings must be reviewed, the allegations discussed, and the underlying facts understood. The discussion of the requirements should be an iterative, consultative process between the client and the intelligence agents, investigators, and analysts.

Planning and Direction. With the requirements understood, the intelligence agents, investigators, and analysts can develop a plan for meeting those requirements, assemble a team specific to that plan, as determined by the skills required and the geography involved, and direct the investigation toward answering the questions that need answering.

Collection. With the right capabilities and resources, the investigative team collects the information from which answers can be extrapolated. Depending on the investigation, this might require the use of open sources, public records, restricted databases, confidential sources, and surveillance.

Processing. The information collected then needs to be processed for analysis. Debriefing reports and surveillance reports might need to be written, photos and videos processed, computer and digital evidence forensically converted to a readable format, books and records entered in spreadsheets, translations and transcripts prepared.

Analysis and Production. Next, the information that has been collected and processed is analyzed and refined to produce an intelligence product that satisfies the requirements of the client, meets the needs of the investigation, and answers the questions. If the collection and processing stages were about finding the dots, then the analysis and production stage is about connecting those dots and being able to articulately report on the picture that emerges.

Dissemination. Like the requirements stage, the dissemination stage should, again, be an iterative, consultative process. There should be a conversation about the intelligence that has been developed. The client can then decide whether additional information is needed or whether newly developed leads should be pursued. In other words, intelligence developed during the first trip through the intelligence cycle often raises new questions to be answered during a second trip through the intelligence cycle. And the cycle continues—planning and directing, collecting, processing, analyzing and producing, and disseminating a new intelligence product.

Law and Ethics

In any conversation about corporate intelligence, it cannot be overstated that the agents, investigators, and analysts, whether engaged by general counsel or by outside counsel on behalf of the company, need to follow the law. Companies continue to find themselves on the receiving end of negative press or a judge’s ire because of the unlawful or unethical tactics of their outside investigators. Cloak-and-dagger corporate espionage may—or may not—make for entertaining television, movies or fiction, but it never makes for good headlines about a company or its lawyers.

Quality Intelligence Enables the Company to Mitigate Legal, Regulatory, and Reputational Risk

The intelligence cycle works because the agents, investigators, and analysts involved in the process understand why the investigation is being conducted; they understand the issues and the questions that need to be answered; they have the capabilities and resources to obtain the information necessary to answer those questions; and they know how to refine that information so it can be acted upon as intelligence or, in litigation, introduced as evidence.

Reprinted with permission from the September 28, 2018 edition of Corporate Counsel. © 2018 ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved. Further duplication without permission is prohibited, contact 877-257-3382 or reprints@alm.com.

Recent Posts

- How GCs Can Use Investigative Consulting To Mitigate Risk, Resolve Disputes, Save Money

- Money Laundering, Sanctions Compliance; What The Binance Case Means

- Sam Bankman-Fried Found Guilty; What Comes Next?

- Sam Bankman-Fried’s Trial Is Almost Over; Here’s What You Need To Know

- Caroline Ellison And Sam Bankman-Fried Are Not Crypto’s Bonnie And Clyde

Categories

- Compliance (5)

- Crisis Management (4)

- Due Diligence (5)

- International (8)

- Investigations (12)

- Litigation (8)

- Press Releases (1)

- Reputation (6)

- Risk (5)

- Sanctions (4)

- Strategy (4)